What Does Inclusive Education Really Mean?

Inclusive education is often misunderstood. Here are some must-haves when defining what it is.

For years—and I mean years—I had a hole in one of my molars.

It’s embarrassing, to tell you the truth.

But a few weeks ago, it started to hurt. Bad. And I couldn’t ignore it anymore. Even though I desperately wanted to. I mean, I went years without it actually bothering me. Food would get stuck in my teeth, but that’s what toothpicks are for right?

Wrong.

Throughout the years, I made a lot of excuses. It was going to cost too much money. I don’t have the time to take care of it. I didn’t want the dentist to judge my lack of action as a character flaw. You name it, it went through my head.

But you know what finally got me to the dentist? It was the pain that forced me to deal with my problem.

And, unfortunately, sometimes it takes a problem that you can’t ignore to get someone to do something.

This relates to inclusive education, in that school districts typically aren’t looking to fix problems that aren’t causing them any pain. Many times, the only reason a school district is encouraged to change is because of a lawsuit, recommendations from a special education audit, or direction from the state department of education.

Last week, we published an article on Think Inclusive about finding your school district’s Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) percentage for students with IEPs in general education for 80% or more of their day.

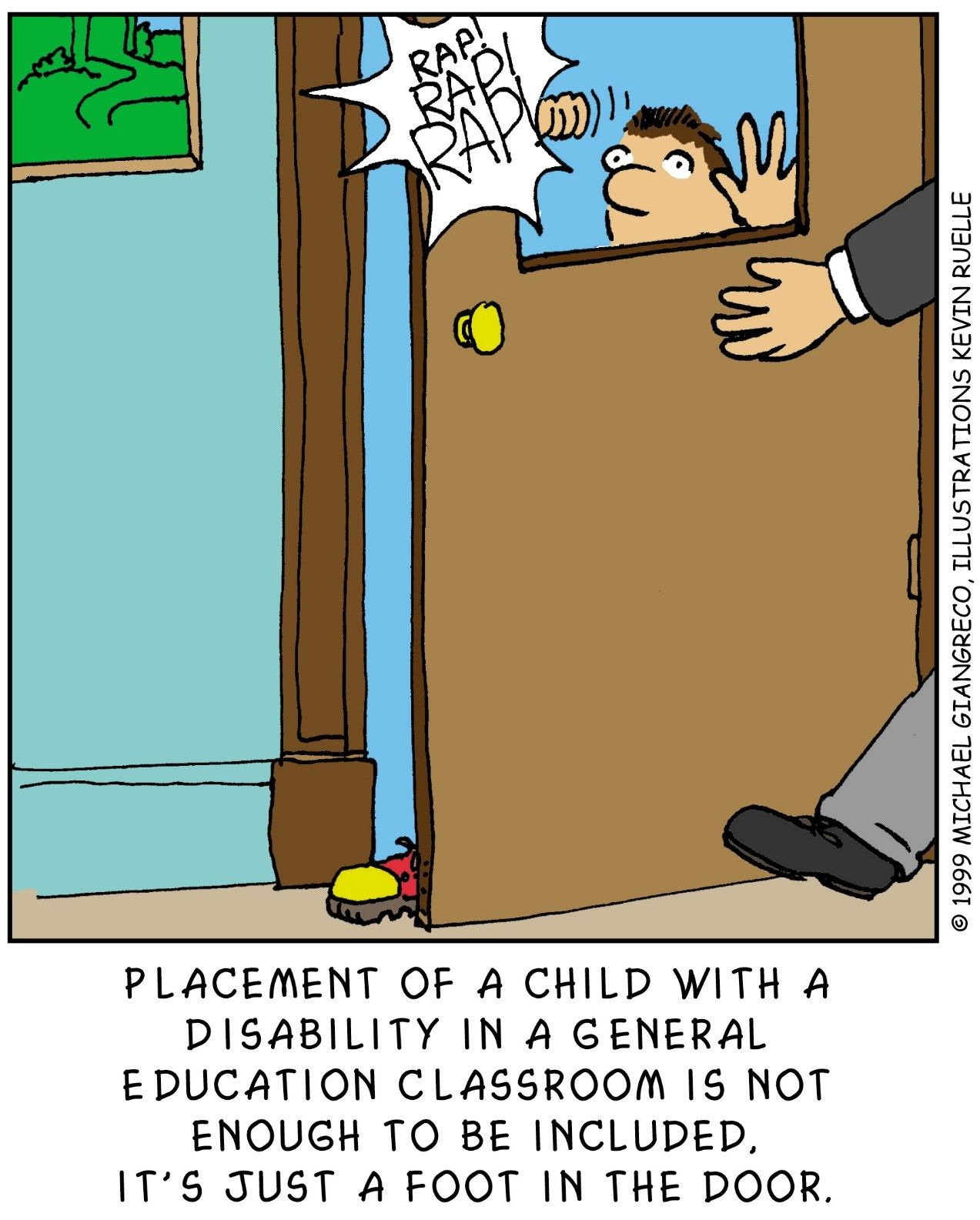

I noted that just because districts have a high percentage of students included in general education classrooms doesn’t mean that they are actually an inclusive school district. Placement is an important part, but only one aspect of inclusive education.

So what does inclusive education really mean anyway?

This post is not meant to be the last word on what inclusive education really is and means. But it is a conversation starter, spurred on from the last edition of The Weeklyish.

Did you do your homework? Did you ask someone to define what inclusive education meant to them? Well, even if you didn’t, I’ll let it slide for one more week.

I love how Villa and Thousand (2016) frame inclusive education, calling it

both a vision and a practice of welcoming, valuing, empowering, and supporting diverse academic, social/emotional, language, and communciation learning of all students in shared environments and experience for the purpose of attaining the desired goals of educaiton. Inclusion is a belief that everyone belongs, regardless of need or perceived ability, and that all are valued and contributing members of the school community.

Check that out. Inclusive education is a vision and a practice. Maybe that’s why it’s hard to define? Because we don’t all share the same vision.

Here is how TASH, an international organization that advocates for human rights and inclusion for people with significant disabilities and support needs, defines it:

All students are presumed competent, are welcomed as valued members of all general education classes and extra-curricular activities in their local schools, fully participate and learn alongside their same age peers in general education instruction based on the general education curriculum and experience reciprocal social relationships.

These are fantastic definitions. And anyone who is an inclusionist should be very familiar with them. But these definitions aren’t the complete picture.

Students with disabilities have to be present in general education classrooms before we can call it inclusive education. We, as educators, have to recognize that the existence of segregated special education classrooms is a barrier to authentic inclusion.

This was a mistake that I first made when was a special education teacher. I could look at both of these definitions of inclusive education and still see enough wiggle room to say that our school or district was inclusive. But I was missing the first step. Sure, I included some of my students in one or two general education classrooms and felt pretty good about that. But what was my school doing to welcome all students in the self-contained classrooms into general education to feel belonging and what did it actually look like?

Educators, you are only one person, which means that in order for you to affect change, you need your friends, allies, and co-conspirators to help.

Here are some indicators from Villa and Thousand (2016) that spell out to what degree your school or district might be inclusive:

Students with disabilities attend the home school or school of choice they would attend if they did not have a disability.

The length of the school day for students with disabilities is not shorter than the length of the school day for students without disabilities

The first placement option discussed for each child with a disability is the general education classroom with all of the necessary supports, specially designed instruction, supplementary aids, and related services.

Students with disabilities are educated alongside their same-age peers without disabilities.

All students regardless of ability have access to the same curricular and extra-curricular activities.

Respectful language, whether (person-first) or (identity-first),* is used when describing students.

School staff presumes competence for all students, especially those who are non-speaking.

General education teachers are provided with and use specific information regard students’ strengths and needs in order to support each student to reach their potential.

Lack of adequate personnel or resources is not used to argue that a student with a disability should be removed from general education.

The need for modifications to the general education curriculum is not used to argue that a student with a disability should be removed from general education.

All student subgroups (i.e. English Learners, students with disabilities, children living in poverty) are making progress on grade-level standards.

Students are supported to learn skills leading to greater independence, self-determination, and self-advocacy.

Across all 13 federal special education eligibility categories and racial/ethnic groups, 90% or more of students with disabilities are educated within general education classes for 80% or more of their day.

Across all 13 federal special education eligibility categories and racial/ethnic groups, 80% or more of students with disabilities receive their instruction in core academic curriculum in general education classrooms rather than in alternative special education content classes.

The percentage of students in the school eligible for special education services mirrors and does not exceed the national, state, or regional percentage.

Wow! I know right? How many indicators of inclusive education is your school district knocking out of the park?

And just a quick note about the above-referenced list. As great as this is, Causton and MacLeod (2021) offer other indicators:

scheduling students in natural proportions: meaning that no one classroom has an overrepresentation of students with disabilities

special and general education teachers co-plan, co-teach, and co-assess with each other

educators use community building in their classrooms to foster belonging

a Univeral Design for Learning framework is used to plan for all students

differentiation is utilized for all students

groupings within classes are heterogenous

engaging instruction is happening for all students

technology is used to support independence, communication, and socialization

YOU: This is great Tim, but what can I do about it?

ME: Did you do your homework?

YOU: My dog ate it.

Y’all. School is starting back up for many students and families this week. There is a lot on our minds as we try to navigate our safety and sanity for this school year.

All you need to get started is to ask some questions.

Here is how that might look.

YOU: (talking to a friend or colleague): Have you heard of this newsletter called The Weeklyish?

FRIEND/COLLEAGUE: No. Never heard of it.

YOU: Oh, it’s great. See, this guy, Tim Villegas—who used to be a special education teacher—writes about inclusion. And this week he wrote about the indicators that make a school inclusive. What comes to your mind when I say inclusive education?

FRIEND/COLLEAGUE: Actually, I’ve never even considered it. // OR // Aren’t we already an inclusive school? We have an inclusion class on my grade level.

YOU: Have you ever heard about this concept called “natural proportions?”

What if we all did that this week?

Seriously. Ask some questions and get back to me on how it went. I’ll even provide a way to submit your homework.

Your dog isn’t that hungry.

Have a great week everyone!

- Tim

*words and emphasis are mine

ICYMI

How to Find a School District's Least Restrictive Environment Percentage

9 Resources for Creating an Inclusive Classroom This School Year

(Podcast) Eric Garcia | We're Not Broken: Changing the Autism Conversation

There's a problem when outcome measures promote "passing."

In The News

UPDATE: Rosie (featured in the Q of the Weeklyish) wins the right to ride the same as her brother.

“Everything’s Gonna Be Okay,” the FreeForm comedy starring an autistic actress, has been canceled after two seasons.

“Born for Business,” a new documentary series featuring entrepreneurs with disabilities, debuts later this month on Peacock.

People with disabilities are 15% of our world. #WeThe15 is a new global movement to transform the world to be more inclusive of the world's 1.2 billion persons with disabilities.

What I’m Reading

What I’m Watching

What I’m Listening To

What’s in my Timeline

From the Wayback Machine

Being Included Without the Needed Supports is Simply Physical Proximity

I read articles written by self-advocates so that I can better understand what my son experiences and how I can help him. But still, most days I can’t begin to fathom what it is like to be my son trying to navigate a world that moves at lightning speed.